Tendon Injuries

Tendon Injuries

There are three sets of muscles which move the thumb and fingers.

The extrinsic flexors curl the digits.

The extrinsic extensors straighten the digits.

The intrinsic muscles fine-tune the balance between the extrinsic flexors and extensors.

Tendons are the white fibrous structures which connect muscles to bones. In the hand, tendons may be very long from the muscle to the insertion (attachment point).

Tendon injuries:

Tendons may be injured in various ways, the most frequent are cuts and blunt trauma. Lacerations to tendons are fairly easy to understand.

With blunt trauma, the attachment of the tendon to bone is overloaded, and the tendon gives way. This not uncommonly occurs with contact sports and ball sports.

Less frequently, tendons can undergo “attritional rupture” as they rub over a bumpy arthritic joint, or a metal plate indiscreetly left by a surgeon.

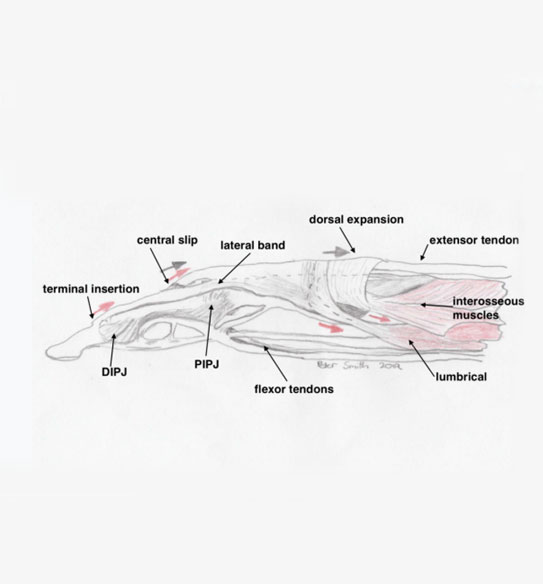

Flexor and extensor tendons of a finger

Flexor tendon injuries

The flexor tendons run from the forearm, through the carpal tunnel (at the wrist) and through long “fibro-osseous tunnels” to their insertions in the digits.

These tendons may be injured anywhere along their course, especially by lacerations.

When the injury occurs inside the tunnels, the treatment is particularly tricky. The repaired tendon tends to try to stick to the walls of the tunnel, preventing gliding and rendering the tendon non-functional. For this reason, this “zone” of tendon injury was known by surgeons as “no-mans land”, and immediate repair was not attempted, due to universally bad results. However, with careful surgery and early mobilisation, reasonable results have been achieved in many, but not all patients.

Refinements in surgical technique have allowed stronger, less bulky repairs. These days, early active motion can often be commenced following early repair of flexor tendon injuries.

If there is a delay to surgery of more than 10 days, or significant injury to the fibrous tunnel, then a two stage repair may be the most reliable option. The standard sequence in this scenario is reconstructing the tunnel’s pulleys over a silicon rod, then returning to exchange the rod for a tendon graft after 3-6 months. The reason for the delay is the need to wait for a slippery synovial layer to form around the rod, for the soft tissues to soften and joints to become pliable. The slippery synovial layer stops the graft from adhering to the fibre-osseous tunnel and ruining the result.

When the FDP (flexor digitorum profundus) tendon is pulled away from bone (“jersey finger”) a repair is usually possible inside of 14 days. If the muscle has become contracted, or it is not possible to advance the tendon through the fibro-osseous tunnel, then a two stage reconstruction may be required. Therefore it is very wise to seek surgical advice as soon as it is realised that a patient is unable to flex the end joint of a finger (DIPJ).

Extensor tendon injuries

The anatomy of the extensor tendons is very different from the flexors, reflecting their different function. The extensors are very thin and do not have a fibro-osseous tunnel system. Much less strength is required from them, as the extensor system is largely postural and an anti-gravity system.

Following surgery for extensor lacerations, specific therapy will optimise the outcome. Usually a splint of some kind will be required for 4-6 weeks. The therapy will depend on the level of injury and the strength of the repair that was possible. Because the tendons are flat in many parts, the surgeon is restricted to simple suture patterns which are less robust. There is a tendency for the injured tendon to try to stick to what’s around it (adhesions) and early motion, as vigorous as is reasonable, will help to minimise this.

Mallet finger

A mallet finger is an injury to the insertion of the extensor into the last bone of the finger (the terminal insertion). This can often occur with a bump, such as moving a mattress, or with a laceration.

Sometimes the tendon is pulled away from the bone, but sometimes the tendon pulls a chunk of bone with it. Only an X-ray will tell the difference (see diagram).

Surgery may be required for lacerations or if there is a large chunk of bone pulled off. Otherwise the best results are achieved with very careful splinting. The splint must hold the DIPJ completely straight, or slightly hyper-extended, for 8 weeks full time. Any flexion of the DIPJ during this 8 week period will ruin the result.

Rarely secondary surgery will help patients who have failed splint treatment. This is either tendon advancement surgery, or occasionally a DIPJ fusion, if the patient wishes to avoid the complex rehab associated with the tendon advancement, and does not mind the idea of losing DIPJ motion permanently (see photo).

Top: X-ray of mallet fracture